Media:

Brittany Tedesco

CPR Communications for Concordia

[email protected]

201.641.1911 x 14

Concordia Care, Inc. Reveals New Corporate Identity: Carisk Partners Provides Specialty Risk Transfer and Quality Care Coordination for Complex Catastrophic Cases

Carisk Partners reflects future vision and evolved business model.

MIAMI – September 12, 2018 – Specialty risk transfer and quality care coordination leader Concordia Care, Inc. (Concordia) announces a new national brand identity designed to reflect its refined business model and strategic vision of bringing end-to-end solutions to the workers’ compensation and auto injury markets. Following a series of coordinated acquisitions, the evolved brand Carisk Partners unifies the merger of Concordia Behavioral Health, a managed behavioral health organization, Concordia Casualty, a specialty risk-transfer company, Atlantic Imaging Group, a nationwide radiology management services company, and the proprietary iHCFA Intelligent Clearinghouse technology.

Beginning September 12, 2018, Concordia will change its name to Carisk Partners (Carisk) and transition all its business entities over a six-month period of time. The name Carisk represents the combined approach of providing quality care coordination with effective risk-transfer solutions. The new logo icon purposefully leverages Concordia’s original “two hearts as one” evolving it to symbolize a balance achieved through their innovative approach.

“We are proud to announce the launch of Carisk Partners, a bold, energetic, and forward-looking company with a brand logo and corporate identity that symbolizes our future and supports our growth,” says Joseph Berardo, Jr., CEO, Carisk. “Too often we see a division between the roles of quality care coordination and risk transfer and our goal is to bridge that gap. The name Carisk marries the combined strength of our organic and acquired products and services under one nationally recognized name as we provide quality care and risk transfer solutions to meet our customers changing business needs.”

Leveraging the collective depth of the behavioral health, imaging, clearinghouse and outcomes business units, Carisk brings over 20 years of experience to the workers’ compensation and no-fault auto markets to improve outcomes and facilitate the closing of claims. Carisk’s Pathways 2 Recovery solution addresses both clinical and behavioral health components in delayed recovery and complex, catastrophic cases.

“The Carisk model is designed for the early identification and intervention of high-risk cases by capturing and analyzing data from multiple source systems, including our Intelligent Clearinghouse solution, and integrating it into an enterprise platform,” continues Berardo.

“Carisk leverages our clinical team’s expertise to develop optimal treatment plans that are executable through our extensive networks of quality specialty providers to improve outcomes and reduce long-term cost of care for our clients.”

He points to the significance of the new logo design, adding, “At the heart of the Carisk model, as represented in our brand logo, is an exceptional team of professionals whose strength comes from a desire to further our mission of providing compassionate care. As a unified organization, we can provide the best care possible for high-risk patients and deliver innovative, end-to-end solutions for our customers and strategic partners.”

Existing brands will also be transitioned in an effort to further unify all products and services under the Carisk name: Carisk Outcomes (formerly Concordia Casualty), Carisk Behavioral Health (formerly Concordia Behavioral Health), Carisk Intelligent Clearinghouse (formerly iHCFA) and Carisk Imaging (formerly Atlantic Imaging Group) will change names on September 12 with no alteration or interruption in services provided.

About Carisk Partners

Carisk (formerly Concordia Care, Inc.) is a specialty risk transfer, care coordination company serving insurers, government entities, self-insured plan sponsors and other managed care organizations. With a foundation in behavioral health, Carisk’s combined end-to-end solutions include risk-transfer and care coordination of delayed recovery and complex, catastrophic cases. Carisk guarantees to improve outcomes and reduce long-term cost of care for its clients by leveraging its biopsychosocial methods, extensive networks of quality providers and proprietary technologies modeled for the early identification and intervention of high-risk patients. Carisk is the first and only Managed Behavioral Healthcare Organization with dual accreditations from both the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Healthcare, Inc. (AAAHC). Visit www.cariskpartners.com to learn more.

Health Care Sharing Ministries: What are the risks to consumers and insurance markets?

By: JoAnn Volk, Emily Curran, and Justin Giovannelli

CommonWealthFund.org –

ABSTRACT

Issue: Health care sharing ministries (HCSMs) are a form of health coverage in which members — who typically share a religious belief — make monthly payments to cover expenses of other members. HCSMs do not have to comply with the consumer protections of the Affordable Care Act and may provide value for some individuals, but pose risks for others. Although HCSMs are not insurance and do not guarantee payment of claims, their features closely mimic traditional insurance products, possibly confusing consumers. Because they are largely unregulated and provide limited benefits, HCSMs may be disproportionately attractive to healthy individuals, causing the broader insurance market to become smaller, sicker, and more expensive.

Goal: To understand state regulator perspectives on regulation of HCSMs and the impact of these arrangements on consumers and markets.

Methods: Analysis of state laws governing HCSMs in all states; interviews with officials in 13 states; and review of the membership requirements and benefits of five HCSMs.

Findings and Conclusions: State regulators voiced concerns regarding the potential risks of HCSMs to consumers and their individual markets. However, in the absence of reliable data describing HCSM enrollment, regulators cannot adequately assess harm. Though limited resources and political constraints have made oversight difficult, all states, regardless of their regulatory approach to HCSMs, should obtain data to better understand the role of HCSMs in their markets.

Background

In a health care sharing ministry (HCSM), members follow a common set of religious or ethical beliefs and contribute — typically monthly — a payment, or share, to cover the qualifying medical expenses of other members.1 An HCSM will then either match paying members with those who need funds for health care costs or pool all of the monthly shares and administer payments to members directly.2 HCSMs have long maintained that they are not health insurance companies and do not guarantee payment for members’ medical claims.3 Since they do not meet the federal definition for health insurance, they are not subject to the consumer protections of the Affordable Care Act.

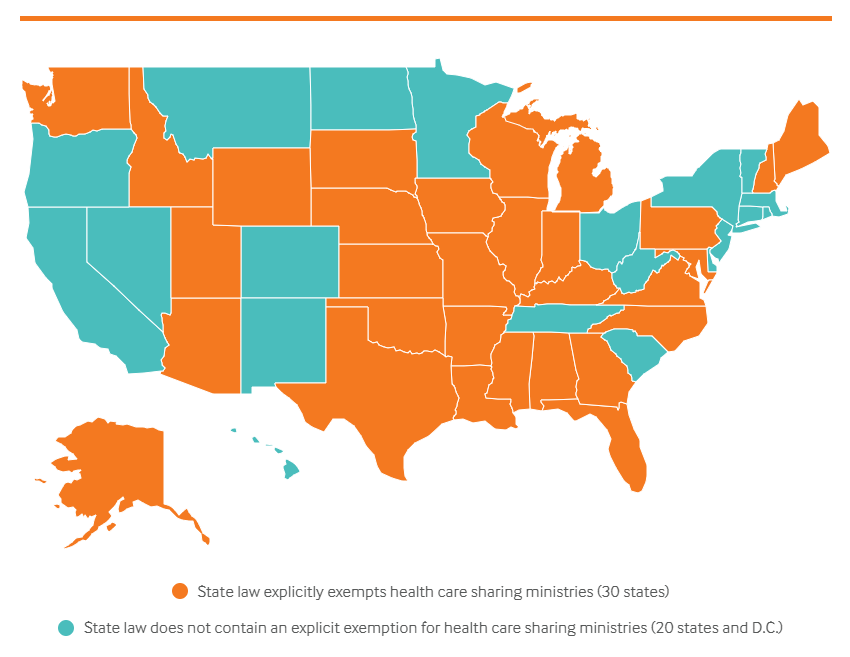

Under the ACA, members in HCSMs are exempted from the federal individual mandate, but the law does not dictate whether and how states may regulate them.4 In particular cases, courts have concluded that HCSM practices constitute the business of insurance, but no state currently treats these entities as insurers.5Thirty states have enacted “safe-harbor” rules that exempt HCSMs from state insurance regulation (Exhibit 1, Appendix 1). Under the safe harbor, as long as an HCSM meets the requirements of the exemption, such as providing a written disclaimer and a monthly statement of member payment requests and contributions, it is, by definition, not engaged in the business of insurance and cannot be required to comply with standards and requirements otherwise applicable to health insurers.

Exhibit 1

State Laws Governing Whether Health Care Sharing Ministries Are Exempt from State Insurance Codes, 2018

Data: Authors’ analysis of state laws governing health care sharing ministries.

Note that states that have not explicitly exempted health care sharing ministries from the state insurance code do not necessarily regulate them.

Source: JoAnn Volk, Emily Curran, and Justin Giovannelli, Health Care Sharing Ministries: What Are the Risks to Consumers and Insurance Markets?(Commonwealth Fund, Aug. 2018).

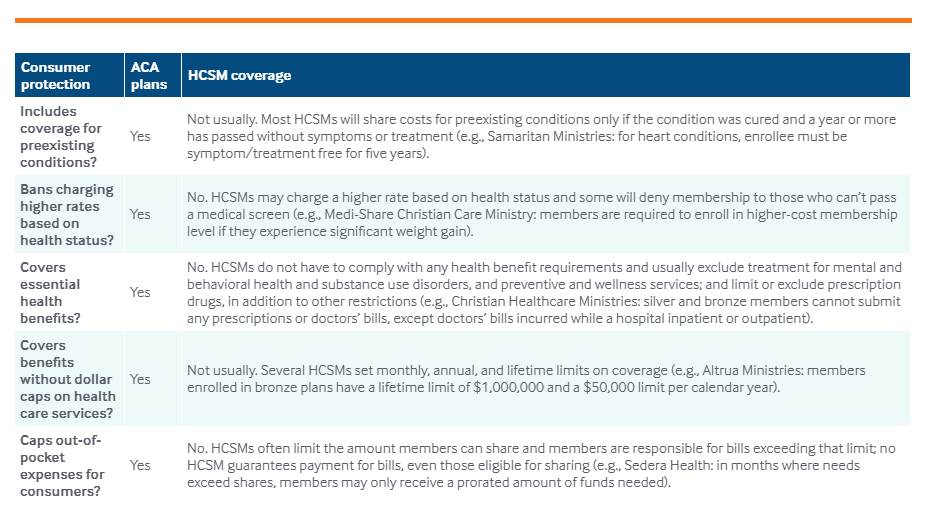

HCSMs have long been an alternative for certain religious communities that object to traditional insurance. The arrangement allows them to share health care cost burdens. Since the passage of the ACA, HCSMs have been marketed more broadly, reaching people who otherwise might not have considered membership.6 While HCSMs may provide value for some people, they also have the potential to create confusion for others, as they closely mimic traditional insurance products, but do not provide the same consumer protections.7 Most HCSMs require payments resembling deductibles, monthly premiums, and copayments, and define a benefits package. Many use provider networks, while some pay broker commissions for selling memberships or offer tiers of coverage similar to ACA-compliant products (i.e., gold, silver, and bronze plans).8 At the same time, because HCSMs are not required to comply with the ACA’s consumer protections, coverage for preexisting conditions may be limited or excluded, medical benefits are typically far more limited than in ACA-compliant plans, and members are never guaranteed payment, even for covered services.9 As with other arrangements that pair low monthly payments with limited benefits, like short-term plans, HCSMs pose a risk of attracting a disproportionate share of currently healthy individuals. If HCSMs draw these consumers out of the ACA-compliant market, they help to create smaller and sicker risk pools in that market, with higher premiums and fewer plan choices (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

Consumer Protections in ACA Plans Compared to Health Care Sharing Ministries

Data: Review of the guidelines of five health care sharing ministries: Altrua HealthShare, Christian Healthcare Ministries, Medi-Share Christian Care Ministry, Samaritan Ministries, and Sedera Health. For more information, see Appendix 2.

Source: JoAnn Volk, Emily Curran, and Justin Giovannelli, Health Care Sharing Ministries: What Are the Risks to Consumers and Insurance Markets? (Commonwealth Fund, Aug. 2018).

Though HCSMs have grown in popularity and sophistication, consumers’ experiences with them and HCSMs’ effects on the traditional insurance markets are not well understood.10 We gathered state regulators’ perspectives on the regulation of HCSMs and data on the impact of these arrangements on consumers and insurance markets. We interviewed officials in 13 states and also examined membership requirements and coverage options offered by five HCSMs (Appendix 2).11,12

FINDINGS

REGULATORS LACK DATA TO UNDERSTAND HCSM OPERATIONS AND IMPACTS

None of the officials we interviewed could say for sure which HCSMs are active in their state or how many individuals are enrolled. Given that HCSMs are typically unregulated and unlicensed, officials have understandably found it difficult to gain even basic information about them. Often, officials become aware that an HCSM is operating through consumer, broker, or provider complaints. Respondents said that such complaints have been rare, but also said that few consumers are aware of the option to complain to state insurance regulators.13 A few states learned of HCSMs when the groups started actively marketing following the implementation of the ACA. Others noted an uptick in marketing during the latest open-enrollment period. States found this to be particularly concerning and received an increase in consumer calls during this time, mostly from people who incorrectly believed they had purchased insurance. Aside from anecdotal evidence, states report that they have few avenues for identifying HCSMs in their areas; as one respondent lamented, “they operate [without oversight] until we find them.”

Since enactment of the ACA, enrollment in HCSMs has reportedly spiked, growing from fewer than 200,000 before 2010 to perhaps 1 million today.14 These estimates are self-reported; there are no independent data available to identify either national or state-level membership. Six states require HCSMs to issue annual audits to comply with their safe-harbor rules, but these reports are limited in scope and do not include enrollment numbers. Some states have attempted to gauge HCSM popularity by tracking local news reporting, combing through HCSM newsletters, or using an HCSM’s total reported medical cost needs and expected member “shares” to infer potential enrollment. In one instance, a state obtained enrollment data directly from an HCSM that is cooperating with an investigation into deceptive broker practices. Aside from these ad hoc approaches, respondents said they have no mechanisms for soliciting information. Many suspected that enrollment is growing based on the number of consumer inquiries, prevalence of HCSM advertising, and sporadic news reports.15 However, no state can pinpoint this trend definitively.

MARKETING AND INSURANCE FEATURES CONTRIBUTE TO CONSUMER CONFUSION

Nearly all respondents believed at least one HCSM was operating in their states. Most expressed concern that some appeared to be functioning in ways that differed from their original intent. Nearly all respondents who noted such concern said that many HCSMs use features that are very similar to insurance and may therefore mislead consumers into thinking they are enrolling in coverage that guarantees payment for a covered claim. Respondents noted that HCSMs have a defined monthly contribution and claims are reimbursed according to a schedule of payment for specific benefits, akin to an insurance contract that requires premiums and pays claims based on covered benefits. Features such as preferred provider networks and marketing during open enrollment — sometimes with the help of paid brokers — also contribute to consumer confusion. A few also noted that some HCSMs were marketing to employer groups — in one case, to a municipal government plan — an approach one respondent suggested was “antithetical to the concept” of the HCSM arrangement.

A POTENTIAL DRIVER OF MARKET SEGMENTATION

In states with active HCSMs, some respondents voiced concerns about the potential for the arrangements to draw healthy individuals from the ACA-regulated market. Generally, respondents suggested there could be risk of market segmentation in the future. Most speculated that membership was too low to have much of an impact; others said that the HCSMs were likely attracting people who have already been priced out of marketplace coverage because they don’t qualify for premium subsidies. Alaska stood out as an exception. Regulators said health care sharing ministry membership is significant (estimated at about 10,000) in the state relative to the individual market (20,000).16 If affordability remains a problem, regulators said that membership in HCSMs could grow big enough to potentially adversely affect the individual market risk pool, particularly in conjunction with other non-ACA coverage options, such as short-term and association health plans, that are expected to draw greater enrollment.

STATES CAN PERFORM OVERSIGHT, BUT OPTIONS ARE CONSTRAINED

Whether or not a state has exempted HCSMs from insurance regulation, regulators may act under certain circumstances to safeguard consumers. Four respondents from states with safe-harbor rules said a threshold consideration was whether the HCSM was in compliance with their safe-harbor criteria. For example, if an HCSM fails to provide required notice to consumers or violates the condition to have a religious component, respondents said they would review the HCSM for activity indicating it was doing business as an unlicensed insurer. One state issued a cease-and-desist order for an HCSM that failed to comply with the religious component of their state’s safe harbor, rendering membership marketing comparable to doing business as an unlicensed insurer. But short of finding an HCSM out of compliance with the safe harbor, regulators were reluctant to take action against it.

Regardless of a state’s safe-harbor status, if a broker misrepresents that an HCSM is insurance or claims that it provides a guarantee of payment, states have the tools and authority to act. Respondents pointed to the state’s authority under their unfair trade practices statutes or a broker suitability standard, which requires brokers to ensure a product is appropriate for a consumer’s needs. One state in this study is working with an HCSM to rein in deceptive broker activity, while others suggested they could refer fraudulent activity to the state attorney general for investigation and potential action.

But most respondents said their options for addressing regulatory concerns and consumer complaints are limited, even in states unconstrained by a safe harbor. One respondent, from a state without a safe harbor, investigates consumer complaints for unpaid claims, but lacks authority to compel an HCSM to respond unless there is evidence of fraud. Other respondents in safe-harbor states suggested it could be difficult for regulators to exercise oversight if legislatures have afforded HCSMs a wide berth. Political support for HCSMs and resource constraints have limited their options for intervening, respondents added.

Some regulators described a reluctance to pursue action without consumer complaints demonstrating harm and noted that even incremental or preliminary action can be met with strong opposition. Regulators in one state had begun taking action against an HCSM for doing business without obtaining a license, but the legislature responded by passing a safe harbor. Another respondent said that legislation to strengthen their safe harbor’s notice requirement had been defeated, making regulators doubtful they could obtain even modest protections for consumers. Following regulatory scrutiny of an HCSM’s operations, a third state’s legislature expanded the definition of HCSMs exempt from state regulation, making the HCSM’s operations legal under the revised safe harbor definition.

DISCUSSION

Some individuals may find value in HCSMs and view them as an alternative to ACA coverage. In particular, for consumers who do not receive marketplace subsidies, HCSM have lower up-front costs. Yet these arrangements carry risks. They may produce unforeseen consequences for members who do not understand what they are buying and who find coverage too skimpy to cover their costs. In addition, consumers in the ACA-compliant market will experience rising premiums and fewer plan choices if HCSMs and other alternative coverage options undermine the risk pool. But it has been difficult to evaluate how these arrangements have worked in practice, given competing priorities, limited resources, and political constraints. In the absence of reliable data on HCSM enrollment, state regulators cannot adequately assess the potential effects on consumers or their individual markets.

At least one reason people consider HCSMs for coverage — lower up-front costs than ACA plans — will likely persist, and increasingly broader marketing of these arrangements can capitalize on that to drive even greater enrollment. In light of the expansion of non-ACA-compliant plans available to individuals buying coverage,17 all states, regardless of whether they have a safe harbor for HCSMs, should collect data — for example, by using audits to obtain membership numbers or monitoring the use of brokers — to better understand the scope and magnitude of HCSMs in their states. States without an exemption may want to go further and review the regulatory framework under which HCSMs operate.

While HCSMs may have previously served a niche market — providing some financial assistance for people who share religious beliefs — many have transformed to give the appearance of traditional insurance. As these entities grow, so too do the risks of consumer confusion, financial exposure, and market segmentation. States should more closely scrutinize whether these arrangements are hewing to their original purpose and the role HCSMs play in a regulated market.

Trump Administration Clears Way for Obamacare Insurer Program

By: Kimberly Leonard

WashingtonExaminer.com – The Trump administration is asking for input on an Obamacare program that collects and pays out billions of dollars to health insurance companies.

To view the original article in its entirety, click here.

Health Problems Reported in 14% of Zika-associated Births in U.S. Territories

Aha.org – About 14% of babies age one or older who were born in U.S. territories to pregnant women infected with Zika virus since 2016 have at least one health problem possibly caused by exposure to the virus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported today. About 6% had Zika-associated birth defects, 9% nervous system problems and 1% both.

To view the original article in its entirety, click here.

Health Care’s Fundamental Flaw and the Recurring-Payment-For-Outcomes Solution

By: Alain C. Enthoven, Russel J. Mueller, & Charles D. Weller

HealthAffairs.org – The fundamental problem that now threatens the health benefits and insurance of everyone in the United States, including Medicare, Medicaid and employee health benefits, is caused by a profound change that has slowly taken place over the last 50 years.

To view the original article in its entirety, click here.

The Battle to end the Cadillac Tax

By: Cort Olsen

EmployeeBenefitAdviser.com – The Affordable Care Act’s high-cost plan tax, popularly known as the Cadillac tax, received bipartisan scrutiny in Congress nearly immediately after the law went into effect in 2010. Although the implementation of the law has been delayed from 2020 to 2022, repealing the penalty could cost the United States roughly $2 billion in lost revenue.

To view the original article in its entirety, click here.

Mayo Clinic Tops U.S. News Hospital Honor Roll for 3rd Straight Year

By: John Commins

Healthleadersmedia.com – For the third consecutive year, Mayo Clinic sits atop the Honor Roll of the nation’s top hospitals, as ranked by U.S. News & World Report.

To view the original article in its entirety, click here.

New Trump Administration Rule Will Require Hospitals Post Prices Online

By: Jessie Hellmann

TheHill.com – Hospitals will be required to post online a list of their standard charges under a rule finalized Thursday by the Trump administration.

To view the original article in its entirety, click here.